CD Roberts

Admin

Posts : 114

Join date : 2013-09-23

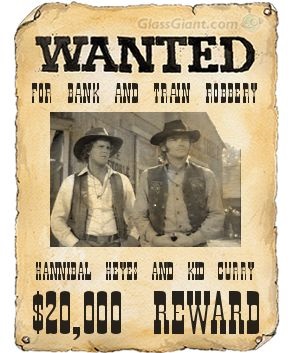

| |  Across the Variola Desert Across the Variola Desert | |

Worn out by a rough journey across the desert, Heyes becomes ill. Worn out by a rough journey across the desert, Heyes becomes ill.

The sun was at its zenith. Crossing the desert had become nearly unbearable; the combination of the heat and the unending sameness of flat bone white sand drained the nearly inexhaustible supply of optimism of Hannibal Heyes. His undergarments were sweat-soaked and sticking to the skin on his back, and around his beltline, and the bandanna tied around his head was now nearly useless as more of the salty fluid dripped down the sides of his face along the angles of his jaw and down his neck. The horizon was a bleak undefined haze with no hills or mountains in sight to break up the monotonous view that emphasized the grim situation.

He felt unnaturally hot as if the air had penetrated his body, and was trapped within unable to exit because it was in equilibrium with the environment. The heat seemed to be affecting his vision, and he blinked to clear it. The result was unsuccessful; his eyes remained dry and scratchy, his vision unfocused. He turned to look at the Kid, and realized unhappily that even his form was becoming indistinct. He returned to looking towards the endless horizon.

He tried to wet his parched lips, and grunted noiselessly at the futility. They hadn’t had a drink in how long? The water was long gone, and the horses had been left behind soon after. The heat and the long hard ride finished them, and he imagined their carcasses were now food for any vultures that lived in this bleak desert. At this rate he and the Kid would be goners too; it was too bad it would be such a miserable death. If he had to die with his boots on why couldn’t it be quick and clean from a bullet?

Something touched his shoulder, and he jerked his hand up to brush at the object only to discover it was the Kid’s fingers tapping on him to rouse his attention. The Kid then pointed off to their right.

“What?” Heyes croaked.

“I think there’s wagons over that way.”

Heyes squinted in the direction the Kid indicated but couldn’t make out anything. He shook his head and shrugged.

“There is. I’m sure of it. C’mon Heyes, wagons means people, maybe fresh horses or at least water. Let’s go.”

He took Heyes by the arm and pulled him along with him towards whatever it was he had seen.

They walked and walked. It was drudgery to lift one foot after the other but giving up wasn’t an option; it never was as far as they were concerned. Heyes shielded his eyes and looked up. The sun was at its zenith.

They neared the wagons which were enveloped in the eerie quiet of the desert. There was no sound and no movement. Heyes rubbed his eyes to clear them. The wagons looked abandoned. The men stopped, and exchanged looks.

“Do we continue?”

“Like you said Kid, there may be water there. Let’s get it and leave.”

They soon realized that the wagons hadn’t been abandoned. There had been an attempt made to circle the four wagons close to each other as if for mutual protection. It was obvious some calamity had occurred, and there was the presence of rot and decay, the canvass shells torn open exposing parts of the wooden skeletons. Lanterns, pans, ribbons, and other objects were strewn about. They could see bodies of humans and animals in the varied positions of death, limbs akimbo. There was the rancid smell of putrefying flesh as they approached the closest wagon. Heyes glanced at a body they passed only long enough to see that it was in male clothing and horribly bloated. Quickly, he averted his gaze, and removing his bandanna from around his forehead tied it across his face, over his nose and mouth. The Kid did the same.

Even through their makeshift masks the smell was nauseating, so nauseating that even in the heat it brought tears to Heyes’ eyes, so that he went from eyes so dry he could barely see to eyes matted and obscured, eyelashes sticking together. He blundered into the wagon, kicked aside the disordered contents, and rubbing his eyes spied a canteen. He grabbed it feeling selfishly grateful that it was heavy with water. In the enclosed area the smell was sickening, and he almost jumped when he realized he was standing foot against another swollen corpse, this one smaller, and in a red checked dress. He didn’t plan to stop to investigate if it was a woman or a child; gagging, he hurried out of the wagon in time to see the Kid jump off the next wagon holding a canteen aloft in triumph.

They walked past more bodies, each man entering one of the two remaining wagons, and each returning with another canteen. Although parched, they walked away from the stench before removing the bandannas and drinking. Heyes figured the heat was really getting to him because he gulped water down until the Kid roughly yanked the canteen away.

“That’s enough, we’re gonna have to spare some of that water if we expect to make it to the next town, you know that.”

“Sorry, Kid. Guess I wasn’t thinking. I’ll be more careful,” and he smiled at his companion ruefully.

The Kid looked at Heyes with an expression of worried suspicion, “are you sick?”

“Nope. Don’t think so at any rate. Just hot. Like I said, I wasn’t thinking. I’m OK, let’s go.”

After some hours walking, Heyes felt as if his body had decided to make a liar of him. His head throbbed and his throat ached when he swallowed. The muscles of his lower back and legs had a soreness that he knew was greater and deeper than could be caused by the long walk. Great, he thought, what I really need on top of all this is the ague. He walked on head bent down staring at his feet, only looking up occasionally to scan the empty horizon through his matted eyelashes.

It seemed as if they had been walking for weeks, not days, and this day seemed unending. He shaded his eyes and glanced towards the sun. It was at its zenith, its blinding rays creating a relentless heat.

“Stop right there.”

He raised his eyes. On the road in front of them stood a lone man, shotgun aimed at himself and the Kid. Behind the man was a town.

How had he missed that? A town? The road? The heat and his ague must be getting to him. If it wasn’t for the Kid they probably would have missed the road. He cleared his throat to speak but could manage no more than a croak. Facing the Kid he held his hand to his throat to indicate he couldn’t speak.

“You got that gun pointed at us for a reason?” the Kid asked wearily.

“Yep, and a darn good one. You two passed that wagon back yonder didn’t you?”

“Well, yeah.”

“You stopped there too, didn’t you? You got all them canteens. Them canteens belonged to them wagons, right?”

“Course they did. We needed the water. But those people were dead when we got there. We didn’t have anything to do with that.”

“Didn’t say you did. But you ain’t coming into our town. Them folks had smallpox, and no one is bringing smallpox into our town.”

The Kid gave Heyes a worried look, and Heyes managed to whisper to him, “look Kid, I’ve got an ague, a sore throat, but I don’t have any pox. Can’t be smallpox.” The Kid nodded.

“Look mister, my friend and me have been walking for awhile since we came across that wagon and we don’t have any pox. We ain’t sick,” he lied, “but we could use some rest and food.”

“You ain’t sick yet, you mean. That wagon train came from S_______. You can just head on over there and get your food and rest there. They already got the pox there. It’s only ___miles away.”

“Mister, you must be joking. We’ve been walking for days and we’re tired. We can’t walk another ____miles.”

The man answered by cocking the trigger of the shotgun.

“OK, OK. We’ll leave. But how about giving us some food?”

The man looked at the two friends mistrustfully. He turned, some time passed, and another man appeared with some supplies. The second man walked a few feet forward, dropping the supplies on the road, and hurried back.

The Kid reached into his pocket and took out some coins.

“Keep it. We don’t want your money; it’s probably tainted with smallpox. Just move on.”

They changed direction, and trudged on to S_________. Going to a town infected with smallpox wasn’t a good idea but they didn’t seem to have much choice. If only it wasn’t so hot. Heyes tried to look ahead and not at his feet, but his vision remained blurred, so he gave it up deciding it didn’t much matter where he looked; he’d rely on the Kid’s judgment to get them to S________. To his relief his aches subsided as they walked. It had been merely an ague that he had been troubled with. He snorted. He hadn’t really been sick after all, and now they had to walk another ____miles. Didn’t really make a difference though, whether he was sick or not, ‘cause that fella back there sure wasn’t going to let them get past him into town.

When he thought about the encounter, Heyes felt a sense of unease. Something just didn’t fit. He pondered for a few moments, and then stopped.

“What’s wrong, Heyes?”

“Kid, where did that second man come from?”

“What?”

“The second man, the one with the food.”

“From the town, of course. Boy, you must really be sick.”

“Well I know he came from the town, but he was just there, all of a sudden.”

“Heyes, you aren’t making any sense. Let’s just get on to S______.”

For a few minutes they plodded on in quiet. Then the Kid asked, “Heyes, S_______, that’s a mining town ain’t it?”

“Yeah, why?”

“Nothin’ really. Just that it must be near the mountains is all.”

“Suppose so.”

Walking, Heyes thought about this. He couldn’t see any mountains, and began to despair. How many miles would they have to walk? It was endless, and worrying about it made his head ache anew. He could feel the sweat running down his face again, and cursed the unrelenting heat. His left palm itched and he scratched at it with his right hand. Even this was a futile effort as both hands were gloved. He was bone weary, and didn’t bother to remove the gloves, letting his mind wander with the itch radiating outward from the center of his palm sometimes towards his thumb, sometimes towards the ring finger, then back to the index finger, but never leaving the center of the hand. He found this fascinating, and played with the fingers bending each in turn to test if that increased the itch. Then he raised his right hand and shielding his eyes, mad a bet with himself, and squinting, peered blearily at the sun. He won his bet. The sun was at its zenith, the blinding rays directed unyieldingly at himself and the Kid.

A couple of hours passed, and as he repeatedly curled and flexed the fingers of his left hand the scratchiness suddenly mutated into pain. Surprised, he stopped, removed his glove and stared at his palm. Directly in the center was a pustule, light red in the center with a large and angry dark red rim. Gingerly he touched it. God it hurt.

A shadow fell over his palm. He raised his head with a blank face mirrored by his partner’s empty eyes.

“Smallpox,” said the Kid.

Heyes nodded. “Maybe you oughta go on without me. Doesn’t make sense for you to get it too.”

“Too late for that. I was around those people at the wagon train too, and anyway we’ve already been sharing food and water. I probably already have it. So it don’t matter. It’s at S______ too if those folks back there were telling the truth.”

“Do you feel sick?”

The Kid shook his head, “nope, but I suppose it’s just a matter of time. Let’s get going. It’ll be better for both of us if we reach S______ before nightfall. Then we can get some help for you and for me if we need it.”

They resumed walking through the lifeless, flat desert.

The outlines of the tent and shack mining town of S______ were directly in front of them, the mountains to the rear and surrounding the sides of it. Heyes almost yelped in frustration. It had come up so suddenly, how had he missed seeing it in the distance? How ill was he? The pain on his palm was spreading, and he could feel pain on his feet, legs, arms and face. Touching his face he could feel the pocks erupting. He was dragging now, barely lifting his feet.

Nearing the town did nothing to alleviate his dread. It smelled dead, there was no other word for it, and it looked dead as well. It was filthy with garbage lying where it was dropped in the streets, the shacks and tents covered with thick layers of dirt; the walls of both oozing a liquid mildew that mimicked mucous. A dog rummaged through a pile of garbage, its ribs protruding, so weak from hunger its legs shook. It ignored the men as they passed tearing at paper wrapped debris.

A miner sat on a chair in front of one of the decrepit shacks, bent forward, humming tunelessly. Coming closer they could see that the skin of his face and hands was littered with peeled scabs. He raised his head, and they saw that his right eye was blinded shut from the scabs. His left eye peered between crusted lids following their movements, demonstrating an iota of curiosity that indicated life remaining.

The miner laughed displaying a mouth filled with blackened and rotten teeth.

“Come to join us, have ya? Got the pox do ya? Well, you’re in the right place.”

“My friend’s sick with it,” said the Kid, “how do I get him some help?”

“Heehee. No help here. Them’s who got it are too sick to help themselves, and them who survived too weak. Come close boy, and let me see your face.”

Heyes neared the man, and the man studied his face. He picked up Heyes’ left arm and pushed his sleeve back to study the pock marks that had risen, and turning it over considered Heyes’ palm which was now a mass of pustules.

“You’re lucky boy. You might live. See these pock marks. See how they don’t touch each other. That’s a good sign.”

“Why?” asked Heyes wearily.

“The smallpox ain’t as bad when them pox is separate. When they’s all blend together feller is probably gonna die, and if they’s so bad they’s inside of ya you die in no time at all. Our doc, he cut up one fella who died fast and that’s what he found, pocks inside. The Indians, they get it even worse; most of ‘em die before the pocks shows up.”

“Where’s your doc?” asked the Kid.

“Heehee. Gone. He got it and went—oh couple of weeks ago now.”

“Well what can I do for my friend?” the Kid demanded in an angry voice devoid of patience.

“Take him to one of the tents. That’s where all the sick is. Can’t do much else. Watch your food and water though, them’s pretty scarce here and someone will steal yours before you can say ‘Jack Robinson.’”

Moving a few feet from the miner Heyes faced the Kid. “Kid, I don’t wanna go to one of those tents, but I’m ready to drop, and we need some kind of shelter. I don’t see any choice.”

“Me neither, so we might as well look for the cleanest one.”

They investigated three of the tents, and found them all equally filthy, reeking of pus, unwashed bodies and disease. On entering the fourth tent Heyes staggered over some bodies and dropped onto his stomach on a space on the ground by the back wall of the tent determined to go no farther. Remembering what the miner had said he hurriedly placed his remaining two canteens under his body. He shifted as best he could in a useless attempt to gain some comfort, turning his head so that he laid his head on its right cheek facing the center of the tent. The Kid sat beside him leaning his back against a wooden table covered with dirty used metal plates. Flies erupted from the plates as the Kid jostled the table. After some moments the flies settled back on the dishes, although a few strays landed on the Kid and Heyes. The Kid swatted away the flies that were on him. Heyes didn’t bother.

He was hot. There was a lit candle on the table dripping wax onto its holder. How could one candle produce so much heat? Through his matted eyes he could see five other bodies lying in the tent. Four showed signs of breathing, chests rising and falling, lips twitching, sounds of swallowing and snorting. The fifth was absolutely still. At least it was against the wall farthest from them. The walls of the tent had the same mildew running down them that they had seen outside. Another reason to keep his head turned from the wall nearest him he thought. It stank. But then so did everything else in the tent from the used plates to the table to the bodies to the pus to the pustules, the scabs, the open sores and of course, the dead body. He wished the Kid would drag the body out, and glanced up at him, but in the poor lighting he couldn’t make out the expression on his face.

The Kid’s breathing had become short and irregular. That meant that the body was going nowhere he figured, and then chastised himself for the thought. What it meant was the Kid was sick now, and that would lessen both their chances of surviving.

He serreptiousisly drew one of the canteens to his lips to take a sip trying to keep the man who was lying closest to him from seeing. The man was on his side facing him. Heyes had the feeling that even in health he would want nothing to do with this man. His curly red hair was a tangled mass, and his face had a look of hatred etched on it. It was a hard face, and had become that way irregardless of illness; Heyes was certain of that. But the man had seen him and his canteen, he was certain of that. He wouldn’t be able to sleep unless the man slept if he wanted to keep enough water to stay alive.

Time passed or at least he thought it did; he was no longer certain. His body was swollen and on fire, covered with hundreds, maybe thousands of the pox. Some were open and oozing, the fluid emanating was truly noxious. The Kid had slumped down along side him. Horror rose in Heyes when he looked at the Kid’s face. The pustules on the Kid’s skin had developed more rapidly than his own, and were merging into large purple masses, many open and draining fluids. The miner had said this was a more deadly form of smallpox, hadn’t he? The Kid was lying with the left side of his face on the ground. He moved suddenly, lifting it, and the result was ghastly. The skin peeled off entirely leaving a large open wound some of it so deep that Heyes swore he saw muscle. He gasped as the Kid dropped down again.

He could barely move, but had to. He needed more water, and he had to remove his boots, something was wrong with the soles of his feet. He struggled to bring his arms to the canteen and to bring that to his mouth. Taking off the cap to the canteen was the work of long minutes. He gulped down some water, cursing when his shaking arms spilled much of it down his chest. He curled into a ball and with frustrating slowness removed his boots and socks. Now he could see the soles of his feet. Like his palms they were covered with the pox, far more than the rest of his body. No wonder they hurt so much. He collapsed on his back, and then carefully turned on his stomach to cover the precious canteens.

He thought vaguely that he should do something for the Kid, but he could hardly help himself. His mind was blank for a moment and then he realized he should give the Kid water. That’s when he realized with despair that he could no longer move his limbs. He could barely turn his head, and what good was that? What was he able to watch?

The candle burnt so brightly. It was half burnt. He wanted to shield his eyes but couldn’t. There was noise, a tinkling sound almost like wind chimes. He looked for the source. Someone had strung up metal forks and spoons. Whatever for? Had they cleaned them and intended to use them again? Whoever had done that was probably a goner. The result was annoying and frightening. The spoons and forks rattled against each other like bones dancing death.

The rattling sounds increased. But there was no wind; it couldn’t be the spoons and forks. Near the opening of the tent, the body of a man jerked spasmodically, and the rattling sounds followed the pattern of his movements. The rattling increased, drowning out the breaths and moans from the other sick men in the room. It came from the man’s throat and chest. As suddenly as the rattling started it stopped, and the man ceased to move.

Heyes felt no sympathy for the now dead man, only a sick sinking feeling that the fetid odor would increase, and that soon his body would contribute to the stink.

Heyes was covered in stickiness, his body engulfed in sweat and purulent oozing. His right eye was swollen shut and encased with pocks. He knew that if he survived he would lose the sight of that eye.

He studied his own breathing. It was jagged and raspy, and his chest burned on exhalation. He focused on a pattern that developed: breathe, swallow, burn, for many minutes this was all that was real. Breathe, swallow, burn, and the candle faded to a dim hazy light with a pale red halo surrounded by blackness. What was incredible was the amount of heat that radiated from it. The heat increased and decreased, hot and warm, then warm and damp, then hot and damp, never dry, always a sticky, wet, putrid heat. Small wonder the sides of the tent were covered with dregs of mildew and mold.

The table also had streaks of brown mildew running down its legs that formed miniature pools of the substance on the ground.

The darkness ebbed enough for Heyes to observe the Kid. Through his crusty lids he could see fluid dribble out of the hundreds of sores on his friend’s face; it seemed as if the Kid’s face was melting. It was disgusting and fascinating at the same time, and he wondered if his appearance was as grotesque. The Kid’s chest quavered incessantly; his mouth gasped for air. Heyes wanted to reach out and stop it, but could barely raise his hand. He couldn’t shut his eyes; he was mesmerized by the terrible sight.

The Kid’s sleeves were rolled up and Heyes could see the skin peeling off, the raw pink musculature open to the dirt and disease filled atmosphere. He could bear it no longer, and with enormous effort twisted his head so he faced “Red”.

Red appeared to be improving. His pustules were now scabs, ulcerated but healing. They obviously itched as he rubbed them until they bled. He had gained strength and was now seated upright. He was drinking from the Kid’s canteen. Even though the Kid was unable to drink from it, Heyes hated Red for stealing the water. Red, sensing Heyes’ ire, sneered at him.

The spoons and forks began to rattle again. Heyes closed his eyes wishing the sound would disappear but it only increased. Soon it was pounding in his head, on and on, growing and throbbing. It was inside his head, and outside his head, louder and louder, and Heyes opened his eyes, and the Kid’s chest rattled and jerked, his hands twitching one finger at a time. Over and over, the sound continued its rhythmic pulsing, until it felt as if it could get no louder, and then it stopped.

The Kid’s chest sank into itself, crumpling, and his eyes started open. Heyes closed his lids; there was no reason to watch the Kid any longer.

Hours passed and Heyes’ body was now a shell of skin stretched from bone to bone filled with heat. He took in more jagged breaths and stared at the candle.

His canteen was gone. He must have fallen asleep. Red had it, and was gulping water from it. Heyes felt red-hot anger towards the man. He had no right to take his water, to pronounce a death sentence on him. His belly burnt with anger, and it gave him a surge of strength. He raised his body, and lurched to Red, bringing his arm down to his chest he stabbed him repeatedly. The action was so sudden Red was dumbfounded, and looked up with a surprised, unresisting expression like a dumb animal brought to slaughter. He let out no sound as blood gushed from the wounds. As Red fell back Heyes ripped the canteen from his now lifeless hand, and rocked back on his heels feeling strange satisfaction with this horrible accomplishment.

He drank the remaining water. It was gone. He threw the canteen aside and almost cried from frustration. Without water he had no chance. He looked down at his right hand which was still covered in blood. He rubbed the blood between his fingers, and then wiped his hand on his shirt tail.

The feeling of satisfaction had faded, and was replaced with growing dread. He had killed a man. Even if he survived the smallpox he would be hanged. Why struggle to recover? Why not just let the smallpox take him?

“That’s not like you Heyes, just to give up like that.”

It was the Kid speaking. He was seated cross-legged, and his flesh was rotting; definitely dead, Heyes thought with morbid interest. Heyes tilted his head so he could see the Kid better with his remaining good eye. And how does one address the dead he mused to himself. Well, he figured, if he wants to talk to me I guess I just talk back, just like its normal, and he laughed at the thought.

“Is there some reason I should bother to go on? I mean, I’m almost dead anyway, and you’re dead. You are dead aren’t you?”

“Well, yeah, that’s what they tell me.”

Heyes gave him a sharp glance.

“Who are they?”

“That’s not important. What’s important is you’re not dead yet.”

“What do you mean, that’s not important? And anyway if I was dead I would know who they were, wouldn’t I?”

“You’re not thinking clearly. You need to rest.” He peeled off a piece of hanging flesh from his left arm.

“I need to rest? Aren’t you supposed to be the one resting, in peace that is?”

“Heyes lie back and I’ll keep watch. Let me help you.” Now the bone was exposed on his arm, and he began to ‘skin’ his hand to the fingertip of his ring finger.

“Kid, no offense, but I don’t think I want your help, not now at any rate.”

“Heyes, lie back, NOW. If you don’t I’ll hold you down.” He leaned towards Heyes as he spoke, and Heyes shrank back from him. His face was so close, peeling and rotting. Heyes couldn’t stand any more, and sank back, shutting his eyes. He tried to wave the Kid away; he could feel his skeletal hands holding his shoulders. He began to shake first in fear, and then his breaths rattled in his chest independent of his fear. The rattling increased and turned into a sick gurgling in his chest. The gurgling increased and he was smothering, drowning. He needed air, but there wasn’t any. The gurgling stopped and his mind went blank.

________________________________________________________________________

Kid Curry and Hannibal Heyes mounted their horses and began to ride from town. The Kid turned to his partner with a frown on his face, and halted his horse. Heyes turned his horse towards him.

“What’s the matter, Kid?”

“Your hat.”

“What?”

“Your hat. Put it on. NOW.”

“What?”

“Heyes, you put your hat on now or we aren’t going anywhere. I just spent two weeks nursing an addled-brained idiot with sunstroke and brain fever who thought he could ride through the desert without his hat on, remember?”

“No need to get so proddy, Kid.”

“No need to get so proddy! I had to take care of you, feed you, clean you, and on top of all that listen to your lunatic ravings. Do you have any idea how repulsive you can be when you are sick?”

“Kid, me—repulsive,” in an offended voice, “just because I have a vivid imagination…”

“Heyes, a vivid imagination doesn’t even begin to describe it. | |

|